I’ve had a number of peak experiences since the release of The Big Payback, some public (like being interviewed on radio and in print) and some more personal (the emails and Tweets and phone calls from friends, family, colleagues and strangers alike).

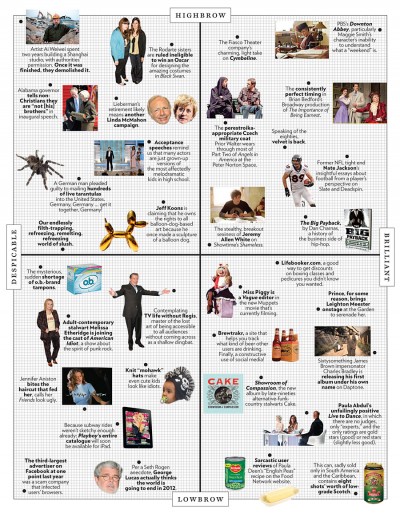

But there’s a special thrill for me in The Big Payback making New York magazine’s “Approval Matrix” this week:

Of course, my Mom and Dad like that the book cover gets to loiter right by the sign that says “Brilliant.”

But, for me, it’s the positioning of the book between “Highbrow” and “Lowbrow” that validates what I was trying to do as a writer, and in many ways reflects the ethos of hip-hop itself, and of the man who first captured its ultimate potential as recorded art, my former boss Rick Rubin.

Those of you who’ve already read the book know that “Album Three,” which is about Def Jam’s ascendance, is divided into two “sides”: “High” and “Low.” Like the title of the book itself, these words carry more than one meaning. In one sense, they are about the ups and then the downs of the relationship between Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons. But they actually derive from Rick Rubin’s artistic philosophy, as explained by the mad genius doorman philosopher of NYU’s Weinstein Hall (and now acclaimed screenwriter), Ric Menello:

During their late-night sessions at Weinstein’s front desk, Ric Menello helped Rubin parse his sense of humor—why Rubin liked comedians like Abbott and Costello and Jerry Lewis, the bluster of pro wrestlers like Rick Flair, the braggadocio of rappers and the insolence of punk rockers. It wasn’t the vulgarity alone, Menello suggested. It was the combination of extreme vulgarity with extremely sophisticated visual and verbal form. It’s art that appears aimed at the cheap seats but also has appeal for the few people who truly see its complexity. Menello knew this to be true, because he had seen another side of Rick Rubin: the young man who revered the beauty of a perfectly executed work of art, the young man who cried at the simple woe of a Roy Orbison song.

“It’s a highbrow-lowbrow game,” Menello said, paraphrasing film critic Andrew Sarris. “Middlebrows beware.”

This theory of “high-low”—paired with a disdain for the “middle,” any- thing tame or tepid—guided Rick Rubin’s artistic endeavors through college and beyond. Rubin aimed to create, in his words, “the worst shit.” But he did it with the intention and all-consuming focus of an artist.

Chuck D., of course, would go on to capture this ethos in a much pithier way: “Reach the bourgeois/and rock the boulevard.” That is indeed what the greatest pop music does: It makes people think while making them dance. And it is what hip-hop did so brilliantly. If you are looking for answers as to why hip-hop was able to succeed where so many other subcultures failed, look to hip-hop’s innate ability to communicate the sophisticated both with words and wordlessly, all while provoking a corporeal, visceral response.

Again, “High-Low” is not the same as “Middle.” It’s not a watering down, nor a blending of the two, nor a compromise. It is the simultaneous, almost paradoxical co-existence of the two. It’s how I came to understand, as difficult as it was for me, why Rick Rubin could produce someone like Andrew Dice Clay. Geto Boys I understood (prurience delivered with excellence). Clay was a harder pill to swallow. But through Rick I came to understand Andrew Silverstein’s character (especially his later, less popular anti-comedy) as a sort of Archie Bunker-on-crack. Rick Rubin always went for art that embodied opposites. Something I didn’t fully understand until, many years later, I sat with Ric Menello at Cozy Soup-n-Burger, interviewing him for the book. Menello, of course, was Rubin’s partner in the writing of Tougher Than Leather, proof that “High-Low” requires deft execution, or else falls far short of the mark. To win, art has to be more than mere provocation (as Dice often fell back into), and more than an inside joke. (And Rick loved to tell and play jokes that no one else got. That was the thrill for Rick. Once, he thought it would be a good idea to address the Warner Music Group convention by having the president at a rival company — Mike Bone of Polygram — read Rick’s speech to the shocked, mute assembly of executives. Fun for few save Rick!)

Of course, I’d love to think of The Big Payback as being part of the “High-Low” tradition — entertaining, enjoyable stories that provide, by implication rather than explication, a larger, more serious meta-narrative. As with hip-hop, there are folks who don’t see much highbrow in it at all. But that’s what I tried to do, anyway. So it’s gratifying to see the book squarely positioned between the two poles on the matrix, and hopefully the result of polarity, not compromise.