Bobby Robinson, the founder of one of the first rap labels, Enjoy Records, and the first record man to sign a bonafide hip-hop act from the streets of the Bronx — Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five — died Saturday at the age of 93.

I was lucky enough to be able to meet and interview the man during the course of researching my book, The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop. When I began my reporting in January of 2007, local papers were reporting that Robinson would soon be evicted from the record shop he had run in Harlem since World War II. And Robinson was getting up there in age, too, so I felt a bit of urgency to get his story.

Getting it wasn’t easy. Robinson — like many others — was tired of giving his jewels away for free, and had the idea that he was going to write a book about his life. So I decided to just hang around for a while instead.

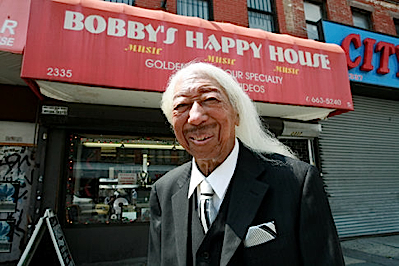

Lucky for me, I only lived three blocks from Robinson’s store, Bobby’s Happy House, a glassy hole-in-the-wall on Frederick Douglass Boulevard around the corner from 125th Street, where his first shop had been. Bobby’s Happy House, as anyone who had been there in the past decade could tell you, had a stream of visitors throughout the day, but nobody ever seemed to buy anything. The display cases were filled with rows of dusty, ancient CDs and cassette tapes. Folks were really coming to see Robinson: tourists from Europe on pilgrimage, neighbors and local characters stopping by between errands, old friends like Paul Winley checking on Bobby. Sometimes, like me, they’d wait for him. Bobby Robinson would usually saunter in mid-day — and what an entrance he would make. At 90, he was always clean, always sharp — usually in a bright-colored suit jacket that contrasted with his long, straight, shock-white hair. He walked slow, turned gradually, and sat tentatively. But when he looked at you, you almost felt zapped. A lot of life and light in those eyes.

I came by throughout 2007, and eventually got to know his daughter and granddaughter, Denise and Lanise Benjamin, who were working very hard to fight eviction at the time. In the meantime, life at the store carried on as it had for years, as sort of a family living room, albeit open to the public. I loved that the whole family called their father/grandfather “Bob.”

Eventually, I was granted a sit-down with the man. I wish I could say it was a great interview. In truth, I barely understood what Robinson was saying half the time, as age had reduced his cadence to a sort of mumbling verbal shorthand. I couldn’t get most of the business details I sought, and Robinson’s response to my question about why he ceded most of his rap business to Sugar Hill Records was simply, “Well, nothing lasts forever.” But I got flashes of his life: Georgia cotton fields, an “ocean of white,” he said. The rugged green mountains of Hawaii against the azure sea and cobalt sky, out of which Japanese planes might fly at any moment. The grey and brown bustle of 125th Street in the postwar years. And records, shellac black with bright labels of every color.

Robinson, of course, would never have remembered that I spoke to him once as a young record executive, when my then-boss Rick Rubin was interested in buying Robinson’s Enjoy Records catalog. Nothing ever came of it, and I never reminded him. I was happy to have had a chance to meet someone who made such an impact on two entirely different genres and eras of music; and someone who, more than anyone, personified Harlem. To repay their kindness, I volunteered to shoot hours of video of Bob for the Robinson family — footage I hope the world will see someday. We got a lot of Robinson’s stories on camera, and preserved some of the look and feel of his store, which closed finally in 2008.

Among the many pictures that Robinson had on his wall — Robinson with a very young Gladys Knight, Robinson with James Brown — I remember one quite clearly. Robinson, in his handsome prime, in full dress uniform, on stage twirling a petite ingénue, lightskinned and beaming, her short skirt lofting to reveal her bare legs. Bob looked so cool, and the girl delighted to be with him.

As much as Bobby Robinson loved Harlem, Harlem loved Bobby Robinson. Even more atrocious than his eviction — just before the bottom fell out during the subprime mortgage crisis — is that the developer who sent him packing has done nothing with the building. It still stands there, empty, boarded up, across from the Duane Reade and around the corner from the Apollo.

I recently asked Lanise how Bob was doing without the shop as part of his daily routine. Surprisingly well, she had said. I am not so sure, however, how we will all do without Bob.

———————————

What follows is a larger passage about Bobby Robinson that didn’t make it into The Big Payback. I’m running it here in its uncondensed version:

Bobby Robinson was usually the first to spot a business opportunity.

During World War II, Robinson was an Army corporal stationed in Hawaii. Nominally, he was in charge of coordinating entertainment for soldiers awaiting to be shipped off to battle in the Pacific, hiring big bands, singers and even a one-legged tap dancer. But Robinson made a killing on the side as a loan shark. By the time the war ended, Robinson had saved over $8,000 in the interest he charged to other servicemen. When the time came to return home to New York, Robinson refused to get on an airplane, instead choosing the safest route for him and his bundle of cash: a battleship. Halfway home, the boat hit a huge storm, and the steel hull shuddered as the ship was thrashed. Oh, me and all my money! Robinson thought as he imagined his ironic, watery grave.

Bobby Robinson, his ear for music, and his savings survived the trip, and in 1946, he became the first colored man to open his own shop on 125th Street. He called it “Bobby’s Happy House,” a record store he funded with $2500 of his wartime stash. In the 1950s, Bobby became one of the first Harlem entrepreneurs to seize on the doo-wop street culture, forming labels like Red Robin and Whirlin’ Disc. In the 1960s, he discovered Gladys Knight & The Pips and produced the first hits by King Curtis on a new label called Enjoy.

But in the 70s, Bobby was slow to realize the business potential of b-beats and MC groups, even though he’d seen the park parties and streetcorner rapping, clear parallels to doo-wop; even though his own nephew, Gabriel — whom everyone called Spoonie — rapped non-stop in Bobby’s apartment, much to the annoyance of Bobby’s wife. Ironically, Spoonie Gee’s first record, “Spoonin’ Rap,” was released by another Uptown record man named Peter Brown. Brown found Spoonie after walking into Bobby’s Happy House one night, shortly after the release of “Rapper’s Delight,” and announcing his intention to produce his own rap record to cash in on the phenomenon.

It took both Spoonie’s record and the torrent of Sugar Hill Gang vinyl moving through his store to finally provoke Bobby to action. But unlike his old friend Sylvia, whose records he once sold out of his shop, Bobby Robinson didn’t create a rap group from scratch. Instead, he used his network of friends to learn a bit about the DJ and MC scene. Who’s the best at this stuff? Bobby asked. His scouts came back from The Bronx with two names: A group named the Funky Four Plus One More, and another crew who called themselves Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five.

The 62-year-old Bobby Robinson cut a conspicuous profile at the back of the Bronx nightclub where he finally found Flash — who thought Bobby was either a cop, or a father on the lookout for his wayward daughter. At the end of the night, after watching Flash and his MCs destroy the crowd, Bobby approached the DJ and proposed that they cut a record together.

The two singles that came out of Bobby Robinson’s initial foray into rap in late 1979 — “Rappin’ And Rockin’ The House” by the Funky Four Plus One More and “Superrappin’” by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five — made Enjoy Records the first label to record reputable artists who had actually emerged from the DJ and MC culture. And while neither record approached the gargantuan success of “Rapper’s Delight,” each sold more than one-hundred thousand copies — a huge windfall for a small operation like Enjoy.

In the months after “Rappers Delight,” other tiny labels and small entrepreneurs followed suit with a flurry of releases that mined the pool of established DJs and MCs from the Bronx and Harlem. Paul Winley released two records from b-beat pioneer, Afrika Bambaataa, without much commercial success, leaving the Bronx DJ feeling burned. The owners of Club 371 put out a record with Eddie Cheba called “Looking Good (Shake Your Body).” Meanwhile, Cheba’s two closest contemporaries and the most successful “rapping DJs” in New York, DJ Hollywood and Lovebug Starski, were earning too much money on the local disco circuit to be bothered with making records.